“Just head for the cone. That’s the lowest part of the fence. Nice and easy.

Little bit left. Keep heading for the cone. There’s only one cone.

Little more left. Just keep looking at the cone.

HEAD FOR THE CONE! THE CONE! THERE’S ONLY ONE FUCKING CONE!

This is my paragliding instructor, Darrell. He got into paragliding about 5 years ago and realised there was a gap in the market teaching this sport, so set up Mount Paragliding, which is still the only game in town (North Island). He’s made it into a community as well as a business. At the time of writing there are 156 members, most of them now fully trained but a lot of the seniors come along for practice weekends to help the beginners. He’s a jovial fellow and most of the time exudes an air of relaxed confidence. Just an occasional slip of the tongue reveals the stresses inherent in coaching 25 novices at a time, and watching them all jump off a cliff one after another.

Here he is offering words of encouragement to a new student.

I signed up as soon as I arrived. I had no choice really.

The paraglider I bought in Wales, but due to lockdown I barely had a chance to use it. Then it was shipped to NZ along with my bike and piano.

This would be a good moment for a montage followed by a fade into me gliding like a pro. Never mind.

Here is a quote from Darrell on the Paragliding whatsapp chat:

“Wow what a fantastic day. So much height and fun. What a great group of people. Thanks for your help Brad. Being around this group is always fun.”

This is typical of conversations on the paragliding whatsapp group. Delve below the obsequiousness, and there’s only more obsequiousness.

Like the majority of practical skills, paragliding didn’t come naturally to me. After a couple of days tuition Darrell asked if I could ride a motorbike, since some of the weight-shift when turning is similar. Cheerily I told him that not only had I tried and failed to learn motorcycling, but it took me 6 attempts to pass my driving test. Darrell didn’t see the humour in this. Let me explain the payment structure: there is a one-off fee, and then you get as much training as necessary until Darrel deems you competent. A couple of online exams later (paragliding theory, meteorology, reading flight maps etc) then you get your international license to fly solo.

If you happen to be a slow learning, this really is an excellent deal.

For those interested in some theory:

Meteorology Study Guide

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1VoYeVYfwQx53WQSrDKL01t46JbHAgm2v/view

Visual Flight Rules Study Guide

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1v5o8YuZWKRxtaS2fDq7kWoRVzEfthFDc/view?usp=drivesdk

Edd’s Guide to paragliding:

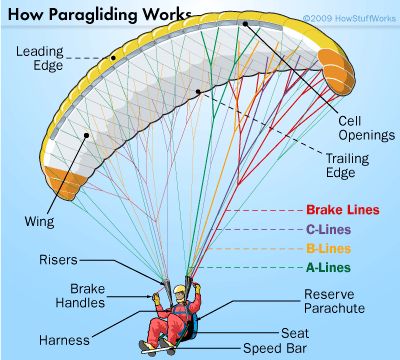

Unlike some paragliding schools I did no tandem flights, it was just me and the glider. Initially you learn to fill the glider with air while it is on the ground in the reverse launch position (facing the glider, with the wind directly behind you) then once the glider is square into the wind and resembling a wall, you raise it overhead using the A-risers. Keep it above you for a while, sterling it left or right to keep the wing inflated if the wind changes. Then when you’ve had enough pull on the C-risers to bring the glider gently back down to the ground.

This skill mastered you move onto raising up the glider, then turn and run down a short bank. Your horizontal velocity will be converted into lift by the glider, and you will be taken just a few feet above the ground, glide along, then come back down and to land, running as you do so. Slow to a stop, turn to face the glider and land it again using the Cs.

You take longer and longer glides over the ground until you feel happy to jump off the cliff and glide down onto the beach, 180 feet below.

When you start getting airborne you can hear the instructor through a 2-way radio.

Turning is easy provided you have plenty of room. Just lean the way you want go and apply a little touch of break on that side.

Landing is important. Just a few necessary technical terms:

Wind speed – this is the is the speed of the wind

Air speed – this is the speed your glider travels through the air. Most gliders have a default speed of 20-23 mph but the pilot can adjust this in flight using the breaks or speedbar.

Ground speed – this is the summation of 2 vectors: wind speed and air speed.

If your glider has an air speed of 15 mph, and you have a tailwind of 7 mph then you will be traveling over the ground at 22 mph. This is not a speed at which you want to hit the ground. Usain Bolt’s max speed is only 23.35 mph and you, dear reader, are no Usain Bolt. Unless of course you are.

So it is always advisable to land into the wind. In this example, landing into wind you will have a ground speed of 8 mph, so you might be able to land running then come to a stop, but to make things easier, when you are just a foot or so above the ground you haul down on both breaks (this manoeuvre is called a “flare”) which stalls the glider bringing it to a stop momentarily and then you drop the last little distance landing graceful on your feet.

My first flight went quite well apart from the landing, when I applied the flare too early and stalled my glider about 12 feet above the ground. The stalled glider dropped vertically and I landed on my behind. The sand was soft and my harness took most of the impact so no harm done. I packed up my glider, climbed the hill and jumped off again.

Weekend after weekend I drove to different corners of the North Island dictated by the winds. After a weekend of excellent flying near Hawke’s Bay, many of the students decided to stick around and fly again on Monday but alas I had to get back for work.

Or did I?

I only had a telephone clinic on Mondays, and I could access all the records remotely. Letting the haematology team know I would be “working from home” I stayed in Hawke’s Bay and phoned my patients in between flights. And I almost got away with it too, until Dixon, one of the consultants, phoned asking me to do a bone marrow biopsy that afternoon. “Errrr, could I do it tomorrow? You see I’m paragliding at the moment on the other side of the island”. Laughing, he said that would be fine.

Reverse Take-off demonstrated by myself (preferable, because you can watch the wing inflate and make sure it’s straight with no lines tangled)

https://drive.google.com/file/d/19eEjwx4BFCDlhhx1lux4Nk4zBd0W1f03/view?usp=sharing

Forward Take-off, me again (used only in low wind because by running, you make the wind)

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1H7DucEx2mXZLVVxpqtDux6SpckXlTDiQ/view?usp=sharing

Soaring: as is clear from this diagram, over the course of the day the land heats up so the air above it begins to rise. This draws air in from the sea often resulting in an onshore breeze. When this strikes an obstacle like a ridge the breeze is obliged to turn skyward resulting in lift which pilots can use to soar backwards and forwards along the ridge. Often for hours at a time.

Soaring is fun to begin with, but after 2 hours of just going back and forth along the ridge doing turns and occasional 360s, the peace and solitude becomes monotonous.

Thermalling:

Thermals, as I’m sure you are aware, are columns of warm air that rise from disproportionately hot patches of land. If you are flying thermals in an unfamiliar area you can try to predict where they might be, for example arising from areas of dark rock or freshly plowed fields. Some of them you can spot since birds of prey will be circling and ascending, and a thermal often terminates at about 5,000 feet with a little tuft of cloud. The altitude at which this happens is called the “dew point”, since moisture in the thermal has cooled to the extent that it forms water droplets.

Having managed to steer your glider into a thermal, you will feel rapid lift and your goal then is to remain in the thermal turning tight 360s until you ride it all the way to the top.

Provided, you’re not heading for a dangerous cloud.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloud_suck

The dreaded Cloud Suck.

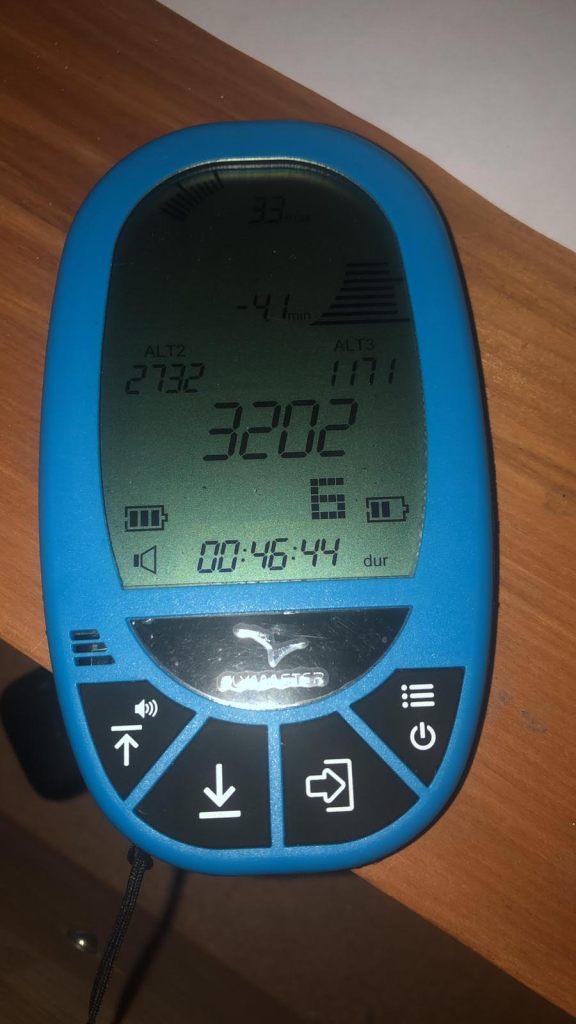

My first day thermalling, I spotted a hawk (I think. It was some sort of bird anyway) circling and ascending so I made right for him(/her). On entering the thermal my new toy, a Velocimeter, started going berserk. This device gives you information about your altitude, rate of ascent or decent, and keeps a log of your flight so you can brag about it afterwards:

(See below)

It also makes amusing computer-game style noises to indicate rate of ascent or descent (high pitched and excited for ascending, low pitched and mournful for descending).

Now rushing upwards, with the velocimeter pip-pipping away, I looked above me and considered the cloud. Hmmm. It didn’t look dangerous. But there was no denying that I had very little idea what I was doing. It shames me to say it, but I did not ride the thermal all the way to the top, and instead lamed-out at only 3,202 feet (my previous max altitude paragliding was 300 feet).

Velocimeter

Did I mention it was a glorious day? After taking in the view I had to decide what to do. Our briefing from Darrel that morning: “if any of you get high enough, then you don’t need to come back and land here. If you have enough altitude to get across that belt of forest then head off that way, catch another thermal if you can and keep going. Land in a field. The farmers around here don’t mind. Wherever you land we’ll come and pick you up”.

Am I high enough to clear the belt of forest? Probably. Worst case scenario, I land in the trees, get stuck and dangle there until rescue comes. I’ve got sandwiches.

The forest was cleared without incident and I began looking for more thermals, first trying a plowed field, then a milk shed, but I only traveled about 3 miles further before landing, not expertly, but quite safely, in a field.

In the next installment: due to a miscalculation when flying, I end up needing surgery under a general anaesthetic. To remove a foreign body.